VFS Layout

Thanks Sergey Klyaus for providing such great VFS diagrams. And I use one of them as cover.

DIO and Page Cache

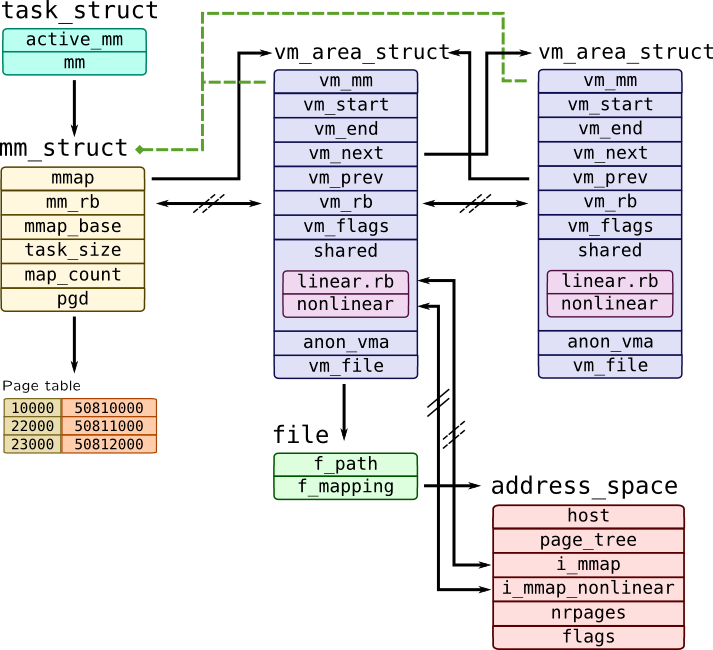

In linux we have memory management system below.

DIO stands for Direct I/O, which is a method of performing I/O operations directly to and from the user-space application buffer without involving the kernel’s page cache. In traditional I/O, data is first read or written to the kernel’s page cache, and then transferred to or from the application’s buffer. Direct I/O bypasses the page cache and directly reads from or writes to the storage device.

Direct I/O is typically used in cases where the data being transferred is large, and the cost of copying it to and from the page cache is significant. It is also useful in cases where applications need to manage their own caching of data, or when the application needs to guarantee that the data is actually written to the storage device and not just cached in memory.

Page Cache

mm/filemap.cmm/filemap.cis a kernel file that provides functions for the management of the page cache, which is a cache of recently accessed pages in memory. The page cache is used to speed up access to files on disk by reducing the number of disk reads required.

Some of the functions provided by mm/filemap.c include:

filemap_fault(): This function is used to handle page faults in the page cache. When a process accesses a page that is not in memory, a page fault is generated and this function is called to allocate and map the page into memory.filemap_read_page(): This function reads a page of data from a file into the page cache. If the page is already in the cache, it is returned without being read from disk.filemap_write_and_wait(): This function writes dirty pages from the page cache back to disk and waits for the write to complete.filemap_write_and_wait_range(): This function writes dirty pages within a given range of the file back to disk and waits for the writes to complete.

These functions are used by the VFS layer and file system implementations to manage the page cache and handle file I/O.

Example on how to use page cache (by VFS)

/*

* Find or create a page at the given pagecache position. Return the locked

* page. This function is specifically for buffered writes.

*/

struct page *grab_cache_page_write_begin(struct address_space *mapping,

pgoff_t index, unsigned flags)

{

struct page *page;

int fgp_flags = FGP_LOCK|FGP_WRITE|FGP_CREAT;

if (flags & AOP_FLAG_NOFS)

fgp_flags |= FGP_NOFS;

page = pagecache_get_page(mapping, index, fgp_flags,

mapping_gfp_mask(mapping));

if (page)

wait_for_stable_page(page);

return page;

}

In the given function grab_cache_page_write_begin(), the mapping argument is a pointer to the address_space data structure that describes the mapping between a file and its pages in the page cache. The address_space structure is used by the file system to interact with the page cache and is associated with each file that is mapped to memory.

The mapping argument is used by the pagecache_get_page() function to locate the page in the page cache associated with the given index offset within the file. If the page does not exist in the cache, it will be created and inserted into the cache by the pagecache_get_page() function using the mapping.

After the page is retrieved or created, grab_cache_page_write_begin() calls wait_for_stable_page() to ensure that the page is in a stable state and can be written to. This is necessary because the page may be undergoing various operations, such as being read from or written to disk, and must be in a consistent state before any further changes can be made to it.

In summary, the mapping argument is essential for interacting with the page cache, allowing file systems to locate, create, and modify pages associated with a specific file.

/**

* pagecache_get_page - find and get a page reference

* @mapping: the address_space to search

* @offset: the page index

* @fgp_flags: PCG flags

* @gfp_mask: gfp mask to use for the page cache data page allocation

*

* Looks up the page cache slot at @mapping & @offset.

*

* PCG flags modify how the page is returned.

*

* @fgp_flags can be:

*

* - FGP_ACCESSED: the page will be marked accessed

* - FGP_LOCK: Page is return locked

* - FGP_CREAT: If page is not present then a new page is allocated using

* @gfp_mask and added to the page cache and the VM's LRU

* list. The page is returned locked and with an increased

* refcount.

* - FGP_FOR_MMAP: Similar to FGP_CREAT, only we want to allow the caller to do

* its own locking dance if the page is already in cache, or unlock the page

* before returning if we had to add the page to pagecache.

*

* If FGP_LOCK or FGP_CREAT are specified then the function may sleep even

* if the GFP flags specified for FGP_CREAT are atomic.

*

* If there is a page cache page, it is returned with an increased refcount.

*

* Return: the found page or %NULL otherwise.

*/

struct page *pagecache_get_page(struct address_space *mapping, pgoff_t offset,

int fgp_flags, gfp_t gfp_mask)

{

struct page *page;

repeat:

page = find_get_entry(mapping, offset);

/*

In the pagecache_get_page function, the find_get_entry function returns an xa_entry_t structure, which may contain either a valid pointer to a struct page or a special value indicating that the page is not present in the page cache. The xa_is_value macro checks whether the value of the xa_entry_t structure represents a valid pointer or not.

If the value is not a valid pointer, i.e., xa_is_value returns true, the page pointer is set to NULL. This indicates that the requested page is not present in the page cache.

If page is still NULL after the xa_is_value check, the function jumps to the no_page label, which is used to handle the case when the requested page is not found in the page cache.

*/

if (xa_is_value(page))

page = NULL;

if (!page)

goto no_page;

if (fgp_flags & FGP_LOCK) {

if (fgp_flags & FGP_NOWAIT) {

if (!trylock_page(page)) {

put_page(page);

return NULL;

}

} else {

lock_page(page);

}

/* Has the page been truncated? */

if (unlikely(page->mapping != mapping)) {

unlock_page(page);

put_page(page);

goto repeat;

}

VM_BUG_ON_PAGE(page->index != offset, page);

}

if (fgp_flags & FGP_ACCESSED)

mark_page_accessed(page);

no_page:

if (!page && (fgp_flags & FGP_CREAT)) {

int err;

if ((fgp_flags & FGP_WRITE) && mapping_cap_account_dirty(mapping))

gfp_mask |= __GFP_WRITE;

if (fgp_flags & FGP_NOFS)

gfp_mask &= ~__GFP_FS;

page = __page_cache_alloc(gfp_mask);

if (!page)

return NULL;

if (WARN_ON_ONCE(!(fgp_flags & (FGP_LOCK | FGP_FOR_MMAP))))

fgp_flags |= FGP_LOCK;

/* Init accessed so avoid atomic mark_page_accessed later */

if (fgp_flags & FGP_ACCESSED)

__SetPageReferenced(page);

err = add_to_page_cache_lru(page, mapping, offset, gfp_mask);

if (unlikely(err)) {

put_page(page);

page = NULL;

if (err == -EEXIST)

goto repeat;

}

/*

* add_to_page_cache_lru locks the page, and for mmap we expect

* an unlocked page.

*/

if (page && (fgp_flags & FGP_FOR_MMAP))

unlock_page(page);

}

return page;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(pagecache_get_page);

The pagecache_get_page() function is used to find and get a reference to a page in the page cache. It takes as arguments the address space mapping, the page index offset, flags to modify how the page is returned (fgp_flags), and the gfp_mask to use for the page cache data page allocation. fgp is an abbreviation for “find get page”. It is used as a prefix for several flags in the pagecache_get_page() function, such as fgp_flags and fgp_mode.

The mapping argument is used to locate the struct address_space associated with the page, which contains information about the underlying storage for the file, such as whether it is stored in memory or on disk.

The offset argument represents the index of the page within the file. The file is divided into pages of a fixed size, and the offset specifies the index of the page within the file.

xa is an abbreviation for extensible array. The extensible array is a data structure used by the Linux kernel to manage page cache. It provides a way to map page indices to pages, allowing efficient indexing of sparse page caches. The xa_is_value macro is a helper function used to check whether an xa_entry is a pointer to a valid struct page or an encoded integer value indicating a hole in the array.

The function first tries to find the page cache entry associated with the given mapping and offset by calling find_get_entry(). If it finds a page, it returns the locked page with an increased reference count. If the page is not found and the FGP_CREAT flag is set, a new page is allocated using the gfp_mask and added to the page cache and the VM’s LRU list. The new page is then returned locked and with an increased reference count.

If the FGP_LOCK flag is set, the page is returned locked, and the FGP_ACCESSED flag marks the page as accessed. If the FGP_FOR_MMAP flag is set, it allows the caller to do its own locking dance if the page is already in the cache or unlock the page before returning if we had to add the page to the page cache.

If the FGP_NOFS flag is set, the function will not perform any file system operations, which can be useful in certain contexts, such as when running in a filesystem-independent context.

If the page has been truncated or the page’s mapping does not match the given mapping, the function will unlock the page, release the reference, and try again by repeating the process.

Overall, the mapping argument is crucial in locating the correct address space and the offset argument is used to locate the correct page within the file, allowing the function to find or create a page in the page cache.

Trivial Details about internal implementation of Xarray

- The general idea is to maintain an extensible sparse array so that you can abstract it, to its user, as a tool that takes an array pointer, an offset and pops out a value.

Maybe you might still get confused about internal implementation on how to get the page from page cache.

In linux/lib/xarray.c we have this xas_load function which “Load an entry from the XArray”.

/*

* Starts a walk. If the @xas is already valid, we assume that it's on

* the right path and just return where we've got to. If we're in an

* error state, return NULL. If the index is outside the current scope

* of the xarray, return NULL without changing @xas->xa_node. Otherwise

* set @xas->xa_node to NULL and return the current head of the array.

*/

static void *xas_start(struct xa_state *xas)

{

void *entry;

if (xas_valid(xas))

return xas_reload(xas);

if (xas_error(xas))

return NULL;

entry = xa_head(xas->xa);

if (!xa_is_node(entry)) {

if (xas->xa_index)

return set_bounds(xas);

} else {

if ((xas->xa_index >> xa_to_node(entry)->shift) > XA_CHUNK_MASK)

return set_bounds(xas);

}

xas->xa_node = NULL;

return entry;

}

/**

* xas_load() - Load an entry from the XArray (advanced).

* @xas: XArray operation state.

*

* Usually walks the @xas to the appropriate state to load the entry

* stored at xa_index. However, it will do nothing and return %NULL if

* @xas is in an error state. xas_load() will never expand the tree.

*

* If the xa_state is set up to operate on a multi-index entry, xas_load()

* may return %NULL or an internal entry, even if there are entries

* present within the range specified by @xas.

*

* Context: Any context. The caller should hold the xa_lock or the RCU lock.

* Return: Usually an entry in the XArray, but see description for exceptions.

*/

void *xas_load(struct xa_state *xas)

{

void *entry = xas_start(xas);

while (xa_is_node(entry)) {

struct xa_node *node = xa_to_node(entry);

if (xas->xa_shift > node->shift)

break;

entry = xas_descend(xas, node);

if (node->shift == 0)

break;

}

return entry;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL(xas_load);

xas array is defined below in include/linux/xarray.h I pull out most important data structure within the xarray.h

/*

* @count is the count of every non-NULL element in the ->slots array

* whether that is a value entry, a retry entry, a user pointer,

* a sibling entry or a pointer to the next level of the tree.

* @nr_values is the count of every element in ->slots which is

* either a value entry or a sibling of a value entry.

*/

struct xa_node {

unsigned char shift; /* Bits remaining in each slot */

unsigned char offset; /* Slot offset in parent */

unsigned char count; /* Total entry count */

unsigned char nr_values; /* Value entry count */

struct xa_node __rcu *parent; /* NULL at top of tree */

struct xarray *array; /* The array we belong to */

union {

struct list_head private_list; /* For tree user */

struct rcu_head rcu_head; /* Used when freeing node */

};

void __rcu *slots[XA_CHUNK_SIZE];

union {

unsigned long tags[XA_MAX_MARKS][XA_MARK_LONGS];

unsigned long marks[XA_MAX_MARKS][XA_MARK_LONGS];

};

};

/*

* The xa_state is opaque to its users. It contains various different pieces

* of state involved in the current operation on the XArray. It should be

* declared on the stack and passed between the various internal routines.

* The various elements in it should not be accessed directly, but only

* through the provided accessor functions. The below documentation is for

* the benefit of those working on the code, not for users of the XArray.

*

* @xa_node usually points to the xa_node containing the slot we're operating

* on (and @xa_offset is the offset in the slots array). If there is a

* single entry in the array at index 0, there are no allocated xa_nodes to

* point to, and so we store %NULL in @xa_node. @xa_node is set to

* the value %XAS_RESTART if the xa_state is not walked to the correct

* position in the tree of nodes for this operation. If an error occurs

* during an operation, it is set to an %XAS_ERROR value. If we run off the

* end of the allocated nodes, it is set to %XAS_BOUNDS.

*/

struct xa_state {

struct xarray *xa;

unsigned long xa_index;

unsigned char xa_shift;

unsigned char xa_sibs;

unsigned char xa_offset;

unsigned char xa_pad; /* Helps gcc generate better code */

struct xa_node *xa_node;

struct xa_node *xa_alloc;

xa_update_node_t xa_update;

};

#define __XA_STATE(array, index, shift, sibs) { \

.xa = array, \

.xa_index = index, \

.xa_shift = shift, \

.xa_sibs = sibs, \

.xa_offset = 0, \

.xa_pad = 0, \

.xa_node = XAS_RESTART, \

.xa_alloc = NULL, \

.xa_update = NULL \

}

/**

* XA_STATE() - Declare an XArray operation state.

* @name: Name of this operation state (usually xas).

* @array: Array to operate on.

* @index: Initial index of interest.

*

* Declare and initialise an xa_state on the stack.

*/

#define XA_STATE(name, array, index) \

struct xa_state name = __XA_STATE(array, index, 0, 0)

And in filemap.c which is mentioned above we define xas in following manner. In short, &mapping->i_pages is array (pointer to the start of pages)

/**

* find_get_entry - find and get a page cache entry

* @mapping: the address_space to search

* @offset: the page cache index

*

* Looks up the page cache slot at @mapping & @offset. If there is a

* page cache page, it is returned with an increased refcount.

*

* If the slot holds a shadow entry of a previously evicted page, or a

* swap entry from shmem/tmpfs, it is returned.

*

* Return: the found page or shadow entry, %NULL if nothing is found.

*/

struct page *find_get_entry(struct address_space *mapping, pgoff_t offset)

{

XA_STATE(xas, &mapping->i_pages, offset);

struct page *head, *page;

rcu_read_lock();

repeat:

xas_reset(&xas);

page = xas_load(&xas);

if (xas_retry(&xas, page))

goto repeat;

/*

* A shadow entry of a recently evicted page, or a swap entry from

* shmem/tmpfs. Return it without attempting to raise page count.

*/

if (!page || xa_is_value(page))

goto out;

head = compound_head(page);

if (!page_cache_get_speculative(head))

goto repeat;

/* The page was split under us? */

if (compound_head(page) != head) {

put_page(head);

goto repeat;

}

/*

* Has the page moved?

* This is part of the lockless pagecache protocol. See

* include/linux/pagemap.h for details.

*/

if (unlikely(page != xas_reload(&xas))) {

put_page(head);

goto repeat;

}

out:

rcu_read_unlock();

return page;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(find_get_entry);

Conclusion for Page Cache

- One

inodehas onemapping.mappingresorts toxato implement a way of indirection to virtual address. Even though virtual address are sparse for each page in page cache,xaenables us to look at it in contiguous perspective. -

xastores pointers to the pages in the page cache, rather than the actual page data itself. The pointers are stored in the internal radix tree nodes of thexa. This allows for efficient searching and access to pages in the cache. - We should look at

generic_file_buffered_read()which is one level higher than page cache. And we should look atfind_get_pages_contig()andfind_get_pages_range(). - Note that

pagecache_get_page()andfind_get_page()are the same thing.

Direct IO

linux/mm/filemap.c

Top level function to write a file with DIO in VFS.

loff_t stands for “file offset” and is used to represent offsets within a file. It is a signed 64-bit integer that can represent file offsets up to 9 exabytes. The loff_t type is used in many places throughout the kernel to represent file offsets, such as in the VFS layer, file systems, and drivers.

pgoff_t stands for “page offset” and is used to represent offsets within an address space. It is an unsigned 64-bit integer that can represent offsets up to 2^64 pages. In the context of the page cache, pgoff_t is used to represent the index of a page within a file’s address space. For example, if a file has a page size of 4KB, then the page with index 0 would start at offset 0 in the file, the page with index 1 would start at offset 4KB, and so on.

mapping should be familiar to you if you read my last section.

/**

* The following comments are borrowed from __generic_file_write_iter, I guess it * breaks a large list of io vectors from BIO to smaller chuncks so that direct

* write don't have to deal with sparse data.

* @iocb: IO state structure (file, offset, etc.)

* @from: iov_iter with data to write

* This function does *not* take care of syncing data in case of O_SYNC write.

* A caller has to handle it. This is mainly due to the fact that we want to

* avoid syncing under i_mutex.

*/

ssize_t

generic_file_direct_write(struct kiocb *iocb, struct iov_iter *from)

{

struct file *file = iocb->ki_filp;

struct address_space *mapping = file->f_mapping;

struct inode *inode = mapping->host;

loff_t pos = iocb->ki_pos;

ssize_t written;

size_t write_len;

pgoff_t end;

write_len = iov_iter_count(from);

end = (pos + write_len - 1) >> PAGE_SHIFT;

if (iocb->ki_flags & IOCB_NOWAIT) {

/* If there are pages to writeback, return */

if (filemap_range_has_page(inode->i_mapping, pos,

pos + write_len - 1))

return -EAGAIN;

} else {

written = filemap_write_and_wait_range(mapping, pos,

pos + write_len - 1);

if (written)

goto out;

}

/*

* After a write we want buffered reads to be sure to go to disk to get

* the new data. We invalidate clean cached page from the region we're

* about to write. We do this *before* the write so that we can return

* without clobbering -EIOCBQUEUED from ->direct_IO().

*/

written = invalidate_inode_pages2_range(mapping,

pos >> PAGE_SHIFT, end);

/*

* If a page can not be invalidated, return 0 to fall back

* to buffered write.

*/

if (written) {

if (written == -EBUSY)

return 0;

goto out;

}

written = mapping->a_ops->direct_IO(iocb, from);

/*

* Finally, try again to invalidate clean pages which might have been

* cached by non-direct readahead, or faulted in by get_user_pages()

* if the source of the write was an mmap'ed region of the file

* we're writing. Either one is a pretty crazy thing to do,

* so we don't support it 100%. If this invalidation

* fails, tough, the write still worked...

*

* Most of the time we do not need this since dio_complete() will do

* the invalidation for us. However there are some file systems that

* do not end up with dio_complete() being called, so let's not break

* them by removing it completely

*/

if (mapping->nrpages)

invalidate_inode_pages2_range(mapping,

pos >> PAGE_SHIFT, end);

if (written > 0) {

pos += written;

write_len -= written;

if (pos > i_size_read(inode) && !S_ISBLK(inode->i_mode)) {

i_size_write(inode, pos);

mark_inode_dirty(inode);

}

iocb->ki_pos = pos;

}

iov_iter_revert(from, write_len - iov_iter_count(from));

out:

return written;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(generic_file_direct_write);

It’s counter part is buffered write (or just write).

ssize_t generic_perform_write(struct file *file,

struct iov_iter *i, loff_t pos)

{

struct address_space *mapping = file->f_mapping;

const struct address_space_operations *a_ops = mapping->a_ops;

long status = 0;

ssize_t written = 0;

unsigned int flags = 0;

do {

struct page *page;

unsigned long offset; /* Offset into pagecache page */

unsigned long bytes; /* Bytes to write to page */

size_t copied; /* Bytes copied from user */

void *fsdata;

offset = (pos & (PAGE_SIZE - 1));

bytes = min_t(unsigned long, PAGE_SIZE - offset,

iov_iter_count(i));

again:

/*

* Bring in the user page that we will copy from _first_.

* Otherwise there's a nasty deadlock on copying from the

* same page as we're writing to, without it being marked

* up-to-date.

*

* Not only is this an optimisation, but it is also required

* to check that the address is actually valid, when atomic

* usercopies are used, below.

*/

if (unlikely(iov_iter_fault_in_readable(i, bytes))) {

status = -EFAULT;

break;

}

if (fatal_signal_pending(current)) {

status = -EINTR;

break;

}

status = a_ops->write_begin(file, mapping, pos, bytes, flags,

&page, &fsdata);

if (unlikely(status < 0))

break;

if (mapping_writably_mapped(mapping))

flush_dcache_page(page);

copied = iov_iter_copy_from_user_atomic(page, i, offset, bytes);

flush_dcache_page(page);

status = a_ops->write_end(file, mapping, pos, bytes, copied,

page, fsdata);

if (unlikely(status < 0))

break;

copied = status;

cond_resched();

iov_iter_advance(i, copied);

if (unlikely(copied == 0)) {

/*

* If we were unable to copy any data at all, we must

* fall back to a single segment length write.

*

* If we didn't fallback here, we could livelock

* because not all segments in the iov can be copied at

* once without a pagefault.

*/

bytes = min_t(unsigned long, PAGE_SIZE - offset,

iov_iter_single_seg_count(i));

goto again;

}

pos += copied;

written += copied;

balance_dirty_pages_ratelimited(mapping);

} while (iov_iter_count(i));

return written ? written : status;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(generic_perform_write);

Probably it’s still nice to show the caller side to this function, which is also in the same file.

// ... something before

loff_t pos, endbyte;

written = generic_file_direct_write(iocb, from);

/*

* If the write stopped short of completing, fall back to

* buffered writes. Some filesystems do this for writes to

* holes, for example. For DAX files, a buffered write will

* not succeed (even if it did, DAX does not handle dirty

* page-cache pages correctly).

*/

if (written < 0 || !iov_iter_count(from) || IS_DAX(inode))

goto out;

status = generic_perform_write(file, from, pos = iocb->ki_pos);

/*

* If generic_perform_write() returned a synchronous error

* then we want to return the number of bytes which were

* direct-written, or the error code if that was zero. Note

* that this differs from normal direct-io semantics, which

* will return -EFOO even if some bytes were written.

*/

if (unlikely(status < 0)) {

err = status;

goto out;

}

// something after ...

Comments on Sparse File and Holes

Sparse Files

Due to their somewhat rare usage, sparse files are often not well understood and a cause of confusion. For example, the VxFS filesystem up to version 3.5 allowed a maximum filesystem size of 1TB but a maximum file size of 2TB. How can a single file be larger than the filesystem in which it resides?

A sparse file is simply a file that contains one or more holes. This statement itself is probably the reason for the confusion. A hole is a gap within the file for which there are no allocated data blocks. For example, a file could contain a 1KB data block followed by a 1KB hole followed by another 1KB data block. The size of the file would be 3KB but there are only two blocks allocated. When reading over a hole, zeroes will be returned.

The following example shows how this works in practice. First of all, a 20MB filesystem is created and mounted:

# mkfs -F vxfs /dev/vx/rdsk/rootdg/vol2 20m version 4 layout 40960 sectors, 20480 blocks of size 1024, log size 1024 blocks unlimited inodes, largefiles not supported 20480 data blocks, 19384 free data blocks 1 allocation units of 32768 blocks, 32768 data blocks last allocation unit has 20480 data blocks # mount -F vxfs /dev/vx/dsk/rootdg/vol2 /mnt2and the following program, which is used to create a new file, seeks to an offset of 64MB and then writes a single byte:

#include <sys/types.h> #include <fcntl.h> #include <unistd.h> #define IOSZ (1024 * 1024 *64) main() { int fd; fd = open(“/mnt2/newfile”, O_CREAT | O_WRONLY, 0666); ...

In the context of file systems, a “hole” refers to an area of a file that has no stored data, but which is treated as if it does. When a program reads from a hole, it reads zeros as if there were actually data there. When a program writes to a hole, it effectively creates a “hole” in the file, which does not take up any space on disk, but which can be read as zeros.

For example, if a program writes a 1KB chunk of data to the middle of a file, leaving a 1MB hole on either side, the file system will allocate only enough disk space to hold the 1KB chunk of data, but will report the file size as 2MB. When a program reads from the beginning or end of the file, it will see zeros, because those parts of the file were never actually written to.

Some file systems may choose to handle writes to holes differently than writes to data that actually exists on disk. In the context of the comment in the __generic_file_write_iter function, it seems to be suggesting that if a write operation falls short of completing, and the file system is set up to handle writes to holes differently than writes to actual data, the function should fall back to buffered writes.

Back to generic_file_direct_write

-

This is top level write.

write_beginandwrite_endin other files folder in different filesystems mount their operations toaddress_space_operations -

io vector is user level buffer sets.

Let’s see an example of no buffer head write begin and end that can be called by function who can be mounted to its address space. This is because we’re in VFS interface (generic interface) and should only provide functionalities and interface that file system needs.

/*

* On entry, the page is fully not uptodate.

* On exit the page is fully uptodate in the areas outside (from,to)

* The filesystem needs to handle block truncation upon failure.

*/

int nobh_write_begin(struct address_space *mapping,

loff_t pos, unsigned len, unsigned flags,

struct page **pagep, void **fsdata,

get_block_t *get_block)

{

struct inode *inode = mapping->host;

const unsigned blkbits = inode->i_blkbits;

const unsigned blocksize = 1 << blkbits;

struct buffer_head *head, *bh;

struct page *page;

pgoff_t index;

unsigned from, to;

unsigned block_in_page;

unsigned block_start, block_end;

sector_t block_in_file;

int nr_reads = 0;

int ret = 0;

int is_mapped_to_disk = 1;

index = pos >> PAGE_SHIFT;

from = pos & (PAGE_SIZE - 1);

to = from + len;

page = grab_cache_page_write_begin(mapping, index, flags);

if (!page)

return -ENOMEM;

*pagep = page;

*fsdata = NULL;

if (page_has_buffers(page)) {

ret = __block_write_begin(page, pos, len, get_block);

if (unlikely(ret))

goto out_release;

return ret;

}

if (PageMappedToDisk(page))

return 0;

/*

* Allocate buffers so that we can keep track of state, and potentially

* attach them to the page if an error occurs. In the common case of

* no error, they will just be freed again without ever being attached

* to the page (which is all OK, because we're under the page lock).

*

* Be careful: the buffer linked list is a NULL terminated one, rather

* than the circular one we're used to.

*/

head = alloc_page_buffers(page, blocksize, false);

if (!head) {

ret = -ENOMEM;

goto out_release;

}

block_in_file = (sector_t)page->index << (PAGE_SHIFT - blkbits);

/*

* We loop across all blocks in the page, whether or not they are

* part of the affected region. This is so we can discover if the

* page is fully mapped-to-disk.

*/

for (block_start = 0, block_in_page = 0, bh = head;

block_start < PAGE_SIZE;

block_in_page++, block_start += blocksize, bh = bh->b_this_page) {

int create;

block_end = block_start + blocksize;

bh->b_state = 0;

create = 1;

if (block_start >= to)

create = 0;

ret = get_block(inode, block_in_file + block_in_page,

bh, create);

if (ret)

goto failed;

if (!buffer_mapped(bh))

is_mapped_to_disk = 0;

if (buffer_new(bh))

clean_bdev_bh_alias(bh);

if (PageUptodate(page)) {

set_buffer_uptodate(bh);

continue;

}

if (buffer_new(bh) || !buffer_mapped(bh)) {

zero_user_segments(page, block_start, from,

to, block_end);

continue;

}

if (buffer_uptodate(bh))

continue; /* reiserfs does this */

if (block_start < from || block_end > to) {

lock_buffer(bh);

bh->b_end_io = end_buffer_read_nobh;

submit_bh(REQ_OP_READ, 0, bh);

nr_reads++;

}

}

if (nr_reads) {

/*

* The page is locked, so these buffers are protected from

* any VM or truncate activity. Hence we don't need to care

* for the buffer_head refcounts.

*/

for (bh = head; bh; bh = bh->b_this_page) {

wait_on_buffer(bh);

if (!buffer_uptodate(bh))

ret = -EIO;

}

if (ret)

goto failed;

}

if (is_mapped_to_disk)

SetPageMappedToDisk(page);

*fsdata = head; /* to be released by nobh_write_end */

return 0;

failed:

BUG_ON(!ret);

/*

* Error recovery is a bit difficult. We need to zero out blocks that

* were newly allocated, and dirty them to ensure they get written out.

* Buffers need to be attached to the page at this point, otherwise

* the handling of potential IO errors during writeout would be hard

* (could try doing synchronous writeout, but what if that fails too?)

*/

attach_nobh_buffers(page, head);

page_zero_new_buffers(page, from, to);

out_release:

unlock_page(page);

put_page(page);

*pagep = NULL;

return ret;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(nobh_write_begin);

int nobh_write_end(struct file *file, struct address_space *mapping,

loff_t pos, unsigned len, unsigned copied,

struct page *page, void *fsdata)

{

struct inode *inode = page->mapping->host;

struct buffer_head *head = fsdata;

struct buffer_head *bh;

BUG_ON(fsdata != NULL && page_has_buffers(page));

if (unlikely(copied < len) && head)

attach_nobh_buffers(page, head);

if (page_has_buffers(page))

return generic_write_end(file, mapping, pos, len,

copied, page, fsdata);

SetPageUptodate(page);

set_page_dirty(page);

if (pos+copied > inode->i_size) {

i_size_write(inode, pos+copied);

mark_inode_dirty(inode);

}

unlock_page(page);

put_page(page);

while (head) {

bh = head;

head = head->b_this_page;

free_buffer_head(bh);

}

return copied;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(nobh_write_end);

So, what’s VFS?

- For VFS, our destination (storage) is memory, can we use page cache, isn’t that redundant?

While it may seem redundant to use the page cache when writing to memory, it is actually an important part of the kernel’s I/O subsystem and provides a consistent and efficient interface for managing memory pages, regardless of where they are stored.

- More importantly, VFS doesn’t handle the storage device directly.

Wait what?

- So what’s the target device for VFS, memory or disk?

he target device for VFS depends on the specific filesystem that is being used. In general, VFS provides a uniform interface for accessing different types of filesystems, including those that use disks as their target storage device (e.g. ext4) and those that use memory (e.g. tmpfs).

When VFS receives a write request, it does not necessarily know whether the target storage device is a disk or memory. The filesystem’s implementation of the write operation will depend on its specific requirements and the nature of its target storage device.

In the case of memory-based filesystems like tmpfs, the page cache is used as an intermediary layer between the VFS and the underlying memory storage device. This allows the filesystem to take advantage of the caching and memory management capabilities provided by the kernel’s page cache subsystem. In contrast, filesystems that target disks typically use their own caching mechanisms and may interact with the disk directly, bypassing the page cache.

- So VFS never handles the read write to file system alone? Must it resort to other file system like tmpfs or ext4?

That’s correct. VFS provides a generic interface for file system operations, but it does not directly handle the storage of files. Instead, it relies on specific file systems such as tmpfs or ext4 to handle the storage and retrieval of data. These file systems implement the file system operations defined by VFS, such as reading and writing data to disk or other storage devices, and provide VFS with the necessary information to manage files and directories in a consistent way across different file systems.

- So VFS is an interface connecting file systems and other subsystems in linux ike memory management system such as page cache, is that correct?

Yes, that’s correct. The VFS provides a standard interface for file systems to interact with the rest of the kernel, including the memory management system (like the page cache) and the system calls used to read and write files. By defining this standard interface, different file systems can be easily added to the kernel and used by applications without needing to know the specific details of each file system’s implementation.

Email : haor2@illinois.edu

Website : http://moomoohorse.com