Doc and Reflection of Linux Kernel Development 3rd Edition

This article is to wildly cite good work of Linux Kernel Development 3rd Edition by Daniel P. Bovet and Marco Cesati.

This article is motivated by my current tasks :

- Create a page cache with Cow (Copy-on-write) enabled for

File System Basics

Historically, Unix has provided four basic filesystem-related abstractions: files, directory entries, inodes, and mount points.

- files

- dentries

- inodes

- mount points

versus

- files

- directories

- control informations

The first group of terms describe a series of abstractions, each of which corresponds to a specific data structure in Linux file system, regardless of which file system it is.

The second group of terms are stuff that file system generally stores, each of which requires one to many items in the first group of terms.

Dentries

Each component of a path is called a directory entry. A path example is /home/wolfman/butter—the root directory /, the directories home and wolfman, and the file butter are all directory entries, called dentries.

struct dentry {

atomic_t d_count; /* usage count */

unsigned int d_flags; /* dentry flags */

spinlock_t d_lock; /* per-dentry lock */

int d_mounted; /* is this a mount point? */

struct inode *d_inode; /* associated inode */

struct hlist_node d_hash; /* list of hash table entries */

struct dentry *d_parent; /* dentry object of parent */

struct qstr d_name; /* dentry name */

struct list_head d_lru; /* unused list */

union {

struct list_head d_child; /* list of dentries within */

struct rcu_head d_rcu; /* RCU locking */

} d_u;

struct list_head d_subdirs; /* subdirectories */

struct list_head d_alias; /* list of alias inodes */

unsigned long d_time; /* revalidate time */

struct dentry_operations *d_op; /* dentry operations table */

struct super_block *d_sb; /* superblock of file */

void *d_fsdata; /* filesystem-specific data */

unsigned char d_iname[DNAME_INLINE_LEN_MIN]; /* short name */

};

Decache

To avoid this time-consuming operation each time this path name is accessed, the VFS can first try to look up the path name in the dentry cache. If the lookup succeeds, the required final dentry object is obtained without serious effort.

Conversely, if the dentry is not in the dentry cache, the VFS must manually resolve the path by walking the filesystem for each component of the path. After this task is completed, the kernel adds the dentry objects to the dcache to speed up any future lookups.

-

Q : there is an dentry name field in dentry, what’s that, can you give me an example to show its relation to path?

-

The

d_namefield in thedentrystructure is astruct qstrthat stores the name of the directory entry (i.e., file name) associated with thedentry. Thed_namefield is used by the file system to compare the name of the directory entry with other names (e.g., during directory lookup operations).Here’s an example to show the relation between

d_nameand path:Suppose you have a file named

foo.txtin the/home/user/Documentsdirectory. When you open the file, the file system looks up the file’s directory entry by traversing the directory tree from the root directory (/) to theDocumentsdirectory, and then searching for thefoo.txtdirectory entry within theDocumentsdirectory. Each directory entry has a name, which is stored in thed_namefield of the associateddentry.So in this case, the

d_namefield of thedentryforfoo.txtin the/home/user/Documentsdirectory would contain the string"foo.txt". The full path to the file would be/home/user/Documents/foo.txt, which is composed of the directory names and file name stored in thed_namefields of thedentriesalong the path to the file. -

Q : Then how can dcache accelerate this process, by hashing?

-

Yes, the

dcache(directory cache) in the Linux kernel can accelerate the file lookup process by using a hash table to storedentries. The hash table allows for constant-time lookup ofdentriesbased on their names, rather than having to traverse the entire directory tree.When a file is looked up, the file system first checks the

dcacheto see if there is adentryfor the file’s directory entry already cached. If there is, the file system can skip the process of traversing the directory tree to find thedentryand instead use the cacheddentryto quickly locate the file.If there is no

dentryin thedcachefor the file’s directory entry, the file system has to traverse the directory tree to find thedentry. Once thedentryis found, it is added to thedcachefor future use. -

wait but like if I have a

foo.txtin/home/user/Documentsand I have anotherfoo.txtinhome/anotheruser/Documents, aren’t there 2 dentries that has the same hash value? -

No, the path got hashed, not only the name. The hash only happens “After the VFS layer goes through the trouble of resolving each element in a path name into a dentry object and arriving at the end of the path, it would be quite wasteful to throw away all that work.”

Hard Link and Symbolic Links

A hard link and a symbolic link (also called a soft link) are two types of links in a file system.

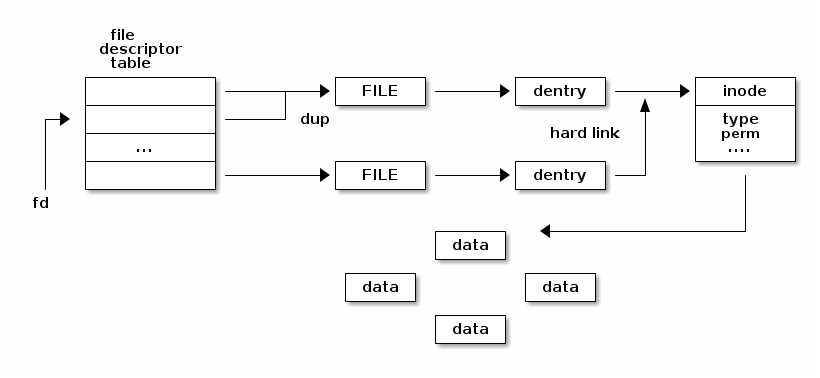

A hard link is a link that points to the same inode object as the original file. When a hard link is created, a new directory entry (i.e., dentry object) is added to the file system that points to the same inode as the original file. The original file and the hard link are essentially two names for the same file, with the same file data, attributes, and ownership. If the original file is deleted, the hard link will still exist and can still be used to access the file data.

On the other hand, a symbolic link is a special type of file that contains a path to another file or directory. When a symbolic link is created, a new directory entry is added to the file system that points to a new inode object that stores the path to the target file or directory. When a process accesses a symbolic link, the kernel reads the link data from the inode object and uses it to find the target file or directory.

The key difference between hard and symbolic links is that hard links point directly to the file data, while symbolic links point to the path of the file or directory. Hard links are restricted to pointing to files within the same file system, while symbolic links can point to files on different file systems or even to remote network resources. Additionally, if the original file is deleted, a symbolic link will become broken, while a hard link will continue to work since it still points directly to the file data.

In summary, hard links create multiple names for the same file data, while symbolic links create a pointer to a path that can lead to different file data.

-

Q : So if I have a dentry pointing to some data block and it has a symbolic link on it (the dentry) and then I delete the file (dentry), I can directly free the resource associated with the dentry (corresponding inode to the file) whereas if I have a hard link on it (dentry), then I have to still hold the resource in inode without freeing it) right?

-

Yes, that’s correct. When you delete a file (i.e., remove its directory entry), the file system checks the link count of the associated inode to determine whether to free the inode and its corresponding data blocks.

In the case of a symbolic link, the link count of the inode is one, because the link is between the directory entry and the inode storing the path to the target file, not between the directory entry and the inode storing the target file’s data. When you delete the file, the link count of the symbolic link inode is decremented to zero, and the inode and its corresponding data blocks can be freed.

In the case of a hard link, however, each directory entry points directly to the inode storing the target file’s data, and each inode has its own link count. When you delete one of the hard links, the link count of the associated inode is decremented, but the inode and its corresponding data blocks are not freed until the link count reaches zero. This is because the remaining hard link(s) still point to the inode and its data blocks.

Nice graphs and articles

-

Really nice figures about file systems and dentries

-

https://msreekan.com/tag/dentry/

-

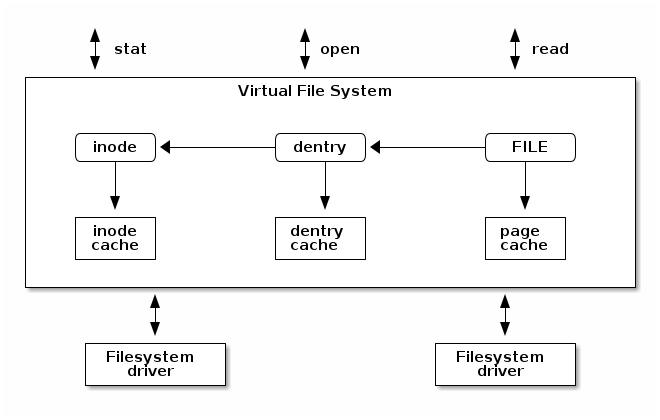

Nice summary about VFS and file systems like below :

-

We can also state that the Linux kernel VFS abstracts the pure logic of how data is represented on the storage device from how it’s viewed by kernel on a running system. In this manner the role of the file system is limited to its core functionality of mapping file access to actual storage blocks and it also deals with the transformation between internal file system specific representation of files to the generic VFS Inode, Dentry and data cache constructs. Eventually, how file is created, deleted or modified and how the associated data cache is managed depends solely on the file system module.

-

-

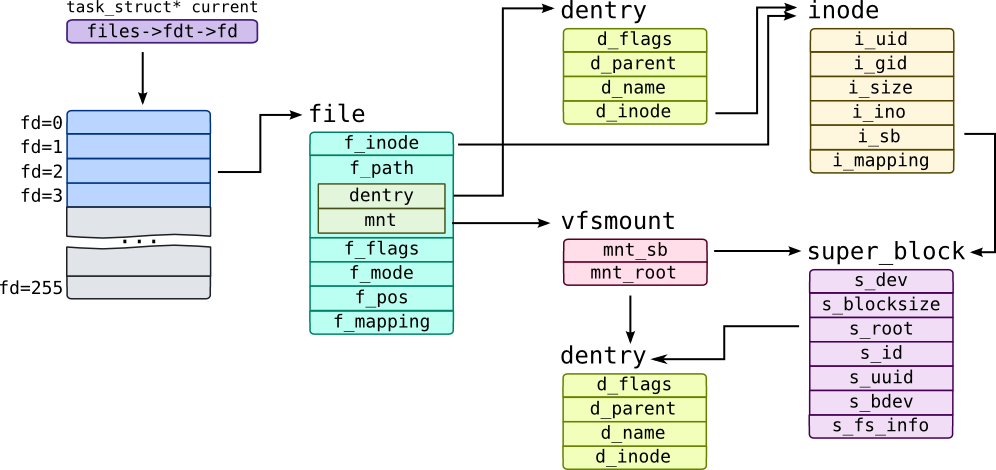

https://myaut.github.io/dtrace-stap-book/kernel/fs.html This guy has lots of amazing data structure representations.

- https://linux-kernel-labs.github.io/refs/heads/master/so2/lec8-filesystems.html Very classic tutorial

I / O scheduling and Request Queues

We explicitly get rid of I / O scheduling in our project because if you want to focus on file system, you don’t focus on schedulers because that’s BIO & device driver’s metrices.

An I/O scheduler works by managing a block device’s request queue. It decides the order of requests in the queue and at what time each request is dispatched to the block device. It manages the request queue with the goal of reducing seeks, which results in greater global throughput.

The modifier “global” here is important.An I/O scheduler, very openly, is unfair to some requests at the expense of improving the overall performance of the system.

I will learn them, probably, later…..

The Page Cache & Page Write Back

The Linux kernel implements a disk cache called the page cache. The goal of this cache is to minimize disk I/O by storing data in physical memory that would otherwise require disk access. This chapter deals with the page cache and the process by which changes to the page cache are propagated back to disk, which is called page writeback.

Back Store

We call the storage device being cached the backing store because the disk stands behind the cache as the source of the canonical version of any cached data.

Read Operation

for example, when a process issues the read() system call—it first checks if the requisite data is in the page cache. If it is, the kernel can forgo accessing the disk and read the data directly out of RAM.This is called a cache hit. If the data is not in the cache, called a cache miss, the kernel must schedule block I/O operations to read the data off the disk. After the data is read off the disk, the kernel populates the page cache with the data so that any subsequent reads can occur out of the cache

- “What’s cached depends on what’s cached”

Write Operation

- One of three strategies:

- no-write : invalidate cached data, writing to disk. Rare beause : failure of caching writes and overhead of invalidating cache.

- write-through cache : update both cache and disk. Advantage : consistency, conherency.

- write-back : write to cache, without directly / immediately updating backing store. Dirty, meaning unsynchronized & Dirty-list. Periodically, pages in the dirty list are written back to disk in a process called writeback, bringing the on-disk copy in line with the inmemory cache.The pages are then marked as no longer dirty.

- “The downside is complexity.”

Cache Eviction

The process by which data is removed from the cache, either to make room for more relevant cache entries or to shrink the cache to make available more RAM for other uses.

Linux’s cache eviction works by selecting clean (not dirty) pages and simply replacing them with something else. If insufficient clean pages are in the cache, the kernel forces a writeback to make more clean pages available.

- Deciding what to evict is impossible for perfection and hard.

LRU

One of the more successful algorithms, particularly for general-purpose page caches, is called least recently used, or LRU.

However, one particular failure of the LRU strategy is that many files are accessed once and then never again. Putting them at the top of the LRU list is thus not optimal. Of course, as before, the kernel has no way of knowing that a file is going to be accessed only once. But it does know how many times it has been accessed in the past.

- the active list and the inactive list

Pages on the active list are considered “hot” and are not available for eviction. Pages on the inactive list are available for cache eviction. Pages are placed on the active list only when they are accessed while already residing on the inactive list.

Non-contiguous disk blocks : page

A page in the page cache can consist of multiple noncontiguous physical disk blocks. For example, a physical page is 4KB in size on the x86 architecture, whereas a disk block on many filesystems can be as small as 512 bytes. Therefore, 8 blocks might fit in a single page. The blocks need not be contiguous because the files might be laid out all over the disk.

Why page cache if we have buffer head?

The purpose of a buffer head is to describe this mapping between the on-disk block and the physical in-memory buffer (which is a sequence of bytes on a specific page). Acting as a descriptor of this buffer-to-block mapping is the data structure’s only role in the kernel.

The Use of Page Cache on 2B SSD

Operation Oriented Analysis

There are two types of operations : Memory Access and Memory Sync.

Memory Access : Read, Write, Mmap

Upon a file read :

- Check the page cache for relevant pages by using

find_get_page_range, this guarantees that we have contiguous up tonr_pagesof pages. - For the holes in the array of cache hits & cache miss $\rightarrow$ fsync the page, to promote the page to page cache.

- Finally read the corresponding range in the file.

Upon a file write :

- Check the page cache for relevant pages by using

find_get_page_range, this guarantees that we have contiguous up tonr_pagesof pages. - For the holes in the array of cache hits & cache miss, add respective pages for them

- Finally write to the page cache

Upon a memory map :

- Check the page cache for relevant pages by using

find_get_page_range, this guarantees that we have contiguous up tonr_pagesof pages. - For the holes in the array of cache hits & cache miss $\rightarrow$ fsync the page, to promote the page to page cache.

- Finally pass the mapped page content to user. (not the wrapper structure with clean page duplicate)

Memory Synchronization : Fsync

- Check the page cache for relevant pages by using

find_get_page_range, this guarantees that we have contiguous up tonr_pagesof pages. - For holes, omit them.

Here we have two strategies :

-

For presented pages, instead of having a duplicate, we directly

block_issuethe page in page cache and evict the corresponding pages. -

For presented pages, initially we keep a duplicate. A duplicate is a clean version of page serving as an operand for XOR paging operation. We XOR the pages to

byte_issue/block issuethem.

The two strategies have trade-off :

- The new method’s cost : Byte Issue + Block issue + Duplicate page + XOR page

- The old method’s code : (With page cache) Block issue’

- The baseline’s code : (No page cache) Byte Issue’’ / (No page cache) Block Issue’’

Implementation : Old page cache methods + Wrapper

- We define a wrapper page struct, with the pointer to the clean page content. We use

container_ofto extract the related structure.

Email : haor2@illinois.edu

Website : http://moomoohorse.com